So, venous congestion is the predominant physiopathology in CHF, with a number of ensuing problems including lung edema, effusions, hepatic congestion and cirrhosis, renal failure and even gut edema and failure, though less traditionally focused on.

Venous congestion is essentially a problem of salt and water, retained by a well-intentioned but (eventually) maladaptive neuro-endocrine process. The bottom line being: too much salt and water…

However, the vast emphasis in pharmacologic CHF management, if you look at guidelines and publications, is predominantly on various neuro-endocrine modulation strategies, and though these certainly have a role, it is logical that optimizing volume status must play a central role. So why is it not a recurrent theme of discussion? Well probably because our means to traditionally assess this is limited. What are the tools used by physicians worldwide to assess congestion? Weight, peripheral edema, JVD, crackles, CXR are pretty much it. Now even under the best of circumstances, these are hardly precise tools, and of intermediate specificity. But it is what is available, and taught, and in most cases, does the job fairly well. However, judging by the problem of recurrent admissions for CHF exacerbations, likely not good enough.

The Canadian HF Guidelines – as thorough as they are – are interesting in that the only time diuretics are addressed are in exacerbation, and a note to use the lowest dose possible to maintain stability… But little else in terms of guiding this assessment of stability or the dosage management. The usual “thorough history and physical” stuff, of course.

So what else could we do? Now my interest in POCUS is no secret, and it seems like the ideal tool for assessing both fluid collections and hemodynamics. So what do we know?

Lungs – at this point it’s beyond much debate, POCUS-enhanced physical examination is vastly superior to radiographs and traditional physical examination. Small effusions are easily seen as well as congestion in the form of B lines. In the case of sub-acute to chronic congestion, as we are not overly concerned with central lesions (not seen with ultrasound), the CXR is of no further benefit.

Peripheral edema – I’ll call this one a tie. Not that much benefit in measuring subcutaneous edema with a probe, except for exact reproducibility, at the cost of time. 😉

The Heart – another no-brainer. Ultrasound wins. With appropriate training, experience, and more important than either, the ability to recognize one’s own limitations.

Venous congestion – Now we’re getting to the interesting stuff. So even if for some, it may be the first time hearing about the clinical use of venous congestion markers in CHF, it isn’t new science. In the 90’s, several studies were published correlating portal vein pulsatility, congestion index, as well as hepatic vein doppler pattern with CVP, RV dysfunction, finding close correlation. In 2016, Iida et al published a great article on renal venous doppler and CHF which I highly recommend reading, and more recently, Andre Denault and William Beaubien-Souligny (@WBeaubien) have been doing tremendous work with portal vein pulsatility and post-op cardiac patients’ organ dysfunction. So the science correlating excessive venous congestion to organ dysfunction is there and is clear.

Why have we not yet widely studied this?

The answer is fairly simple. Prior to the growth of POCUS, there was no single clinician group holding the necessary set of clinical and echographic skills to make this clinical routine. Cardiologists are not all echo-capable, and even those that are would have had little or no experience dopplering abdominal organs and vessels. Radiologists – most of the literature coming from their field – are not pharmaco-clinicians and do not follow patients. Family physicians and internists, likely the bulk of the physicians looking after these patients, largely had not had access to or echo skills. Until now.

So a quick review: right-sided failure causes elevated RAP, so everything upstream gets congested. The first echo signal of this is the plethoric IVC (in both axes of course!!!), and an abnormal hepatic vein doppler (which is pretty much like a CVP tracing, just non-invasively) but is that the max? Nope. What is worse is when that pressure transmits thru backwards from hepatic veins to portal vein, transforming a normally monophasic flow with minimal variation into a progressively more pulsatile flow, to the eventual point of being intermittent. And when the IVC pressure transmits across a congested kidney such that the same thing occurs in the renal veins.

Those findings have been well studied and correlate with poor outcomes in CHF.

So what could we do?

What we are doing now is systematically assessing CHF patients in terms of their venous side. What we see so far is that some have full, plethoric IVCs, maybe B lines and effusions, maybe some peripheral edema, but may or may not have those worse markers of abnormal doppler flows, and those who don’t generally don’t have significant organ dysfunction such as renal failure (I discussed this a few years ago in my pre-doppler era in terms of re-thinking common approaches).

So when we find significant portal pulsatility, we diurese aggressively, creatinine notwithstanding. We almost always get an improvement in biochemical markers of renal function within 48-72 hours, with the only really tricky patients being those with severe pulmonary hypertension. More on that in another post.

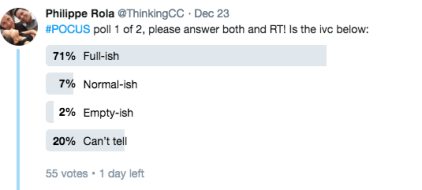

Goonewardena et al had a really great observational study that showed that if CHF patients were discharged with a non-plethoric IVC and significant respiratory variation, they were less likely to be re-admitted. The figure below on the right shows the numbers:

So there is reasonable evidence to suggest a POCUS-guided approach, which we’ll go over in the next post, which should include our revised Advanced CHF Clinic guidelines.

I can already hear the thoughts… “is there any evidence for this?” But those asking that reflexively should first ask themselves “what is the evidence behind the way I assess congestion and manage CHF?”

cheers

Philippe

Refs

Portal vein pulsatility and CHF

Iida et al. article

Beaubien-Souligny and Andre Denault open access article